Porto, Portugal | 17 June]

Abstract

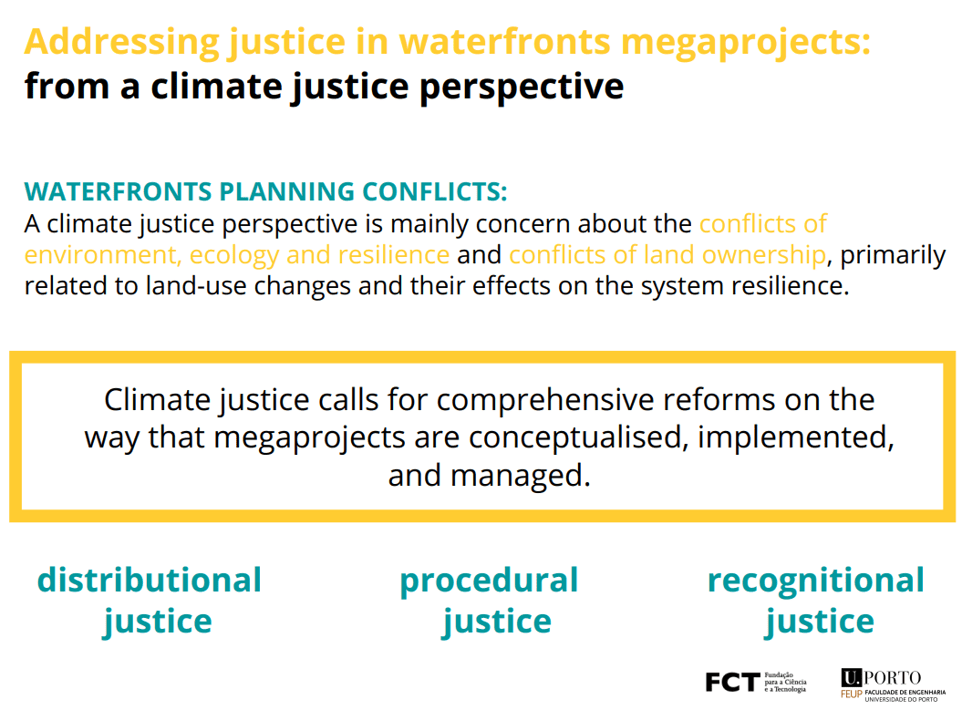

Waterfront’s megaprojects are considered a flagship of the neoliberal movement, reflecting changing forms of labour and manufacturing (Harvey 1989; Sager 2011; 2015). Waterfront redevelopment carries out relevant cultural, environmental, and economic functions. However, several planning conflicts have been identified related to land ownership, heritage and culture, social and environmental justice, and environment and resilience, among others(Avni and Teschner 2019). Due to climate change, growing concerns over climate and environmental justice will continue to challenge waterfronts in the future (Bautista et al. 2015; Mohai, Pellow, and Roberts 2009). Within Europe, the European Landscape Convention (Déjeant-Pons 2006) has reinforced the debate regarding the concept of the landscape itself but especially providing a way of understanding the relationship between ideas of justice and the practice of landscape (Groening 2007; Olwig 2007). Based on a comprehensive review of the state-of-the-art literature, this essay focus on how can planning address climate and environmental justice in waterfront developments in general and through the European Landscape Convention in particular. Conclusions show the advantages of addressing climate and environmental justice through a landscape lens in waterfronts.

References

Avni, Nufar, and Na’ama Teschner. 2019. “Urban Waterfronts: Contemporary Streams of Planning Conflicts.” Journal of Planning Literature 34 (4): 408–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885412219850891.

Bautista, Eddie, Eva Hanhardt, Juan Camilo Osorio, and Natasha Dwyer. 2015. “New York City Environmental Justice Alliance Waterfront Justice Project.” Local Environment 20 (6): 664–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2014.949644.

Déjeant-Pons, Maguelonne. 2006. “The European Landscape Convention.” Landscape Research 31 (4): 363–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/01426390601004343.

Groening, Gert. 2007. “The ‘Landscape Must Become the Law’—or Should It?” Landscape Research 32 (5): 595–612. https://doi.org/10.1080/01426390701552746.

Harvey, David. 1989. “From Managerialism to Entrepreneurialism: The Transformation in Urban Governance in Late Capitalism.” Geografiska Annaler. Series B, Human Geography 71 (1): 3. https://doi.org/10.2307/490503.

Mohai, Paul, David Pellow, and J Timmons Roberts. 2009. “Environmental Justice.” Annual Review of Environment and Resources 34: 405–30. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-082508-094348.

Olwig, Kenneth R. 2007. “The Practice of Landscape ‘conventions’ and the Just Landscape: The Case of the European Landscape Convention.” Landscape Research 32 (5): 579–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/01426390701552738.

Sager, Tore. 2011. “Neo-Liberal Urban Planning Policies: A Literature Survey 1990-2010.” Progress in Planning 76 (4): 147–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progress.2011.09.001.

Sager, Tore. 2015. “Ideological Traces in Plans for Compact Cities: Is Neo-Liberalism Hegemonic?” Planning Theory 14 (3): 268–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095214527279.

Funding

Carla Gonçalves was funded by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) through the Doctoral Grant UI/BD/151233/2021.